In shaping my debut book’s complex characters, I found that what truly makes a house is about much more than picking the right wall color.

When I was writing my debut novel, The Ones We Loved (out May 6 from Park Row/Harper Collins), I spent quite a long time helping each character pick out their house and choose what furniture to place inside. These spaces would mirror the characters’ states of rest and unrest, so they had to be familiar and malleable. Shaping them showed me that designing a home is about much more than picking the right colors for walls and placing your plants in the right corners for the best light—it’s an act of self-creation.

My novel is a love story, and it’s also about the connections we nurture with the people who live next door. Because we notice each other, we decide to care for one another. That is the binding thread shared by the inhabitants of The Ones We Loved. Some of their homes were constructed with the aid of neighbors who helped dig foundations and lay bricks; others were made by new arrivals who preferred to work on their projects alone; a few were inherited from older relatives who had built them with the hopes that these houses would always be filled with kin. What made them homes—places to seek out refuge, return to and run from—was different for each one. For a widow and her daughter, a particular stool made their home both blessed and ordinary because of how it had been delivered to their door after a prayer; an elderly couple shared their home with an evergreen mulberry tree that shaded their greatest loves; and one boy carefully wove and dyed the mats that lined the floors he walked over with his two closest friends.

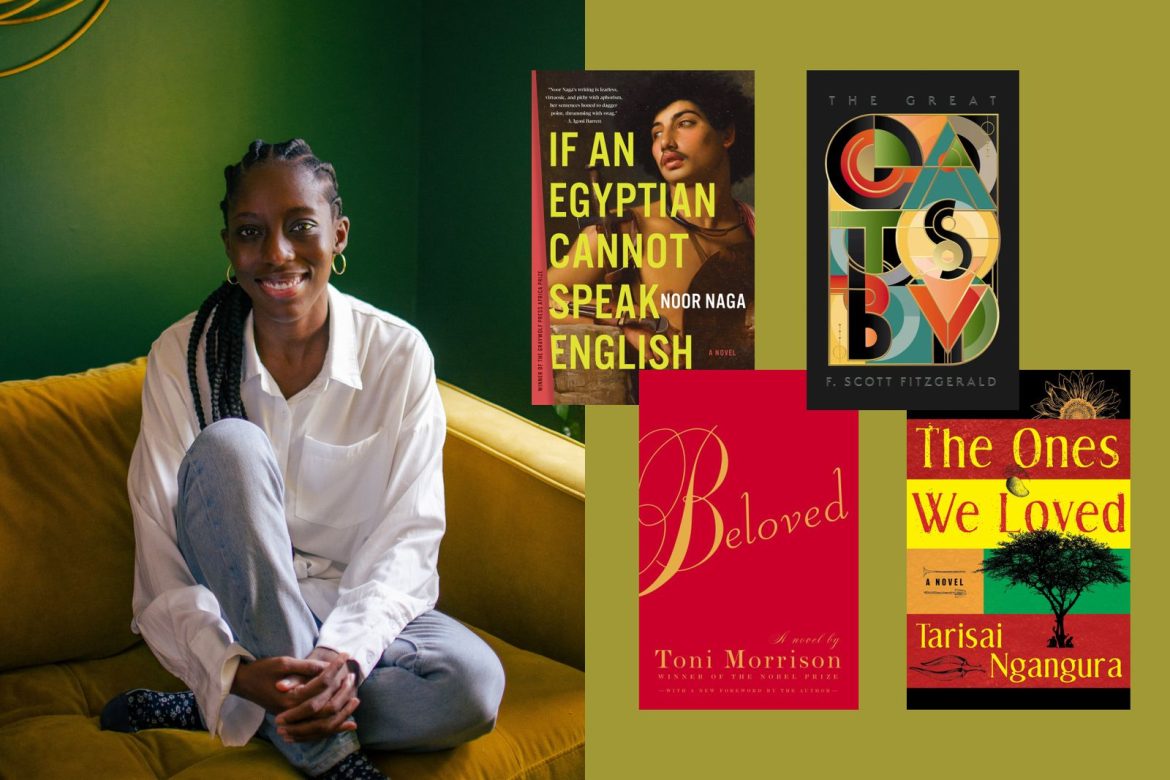

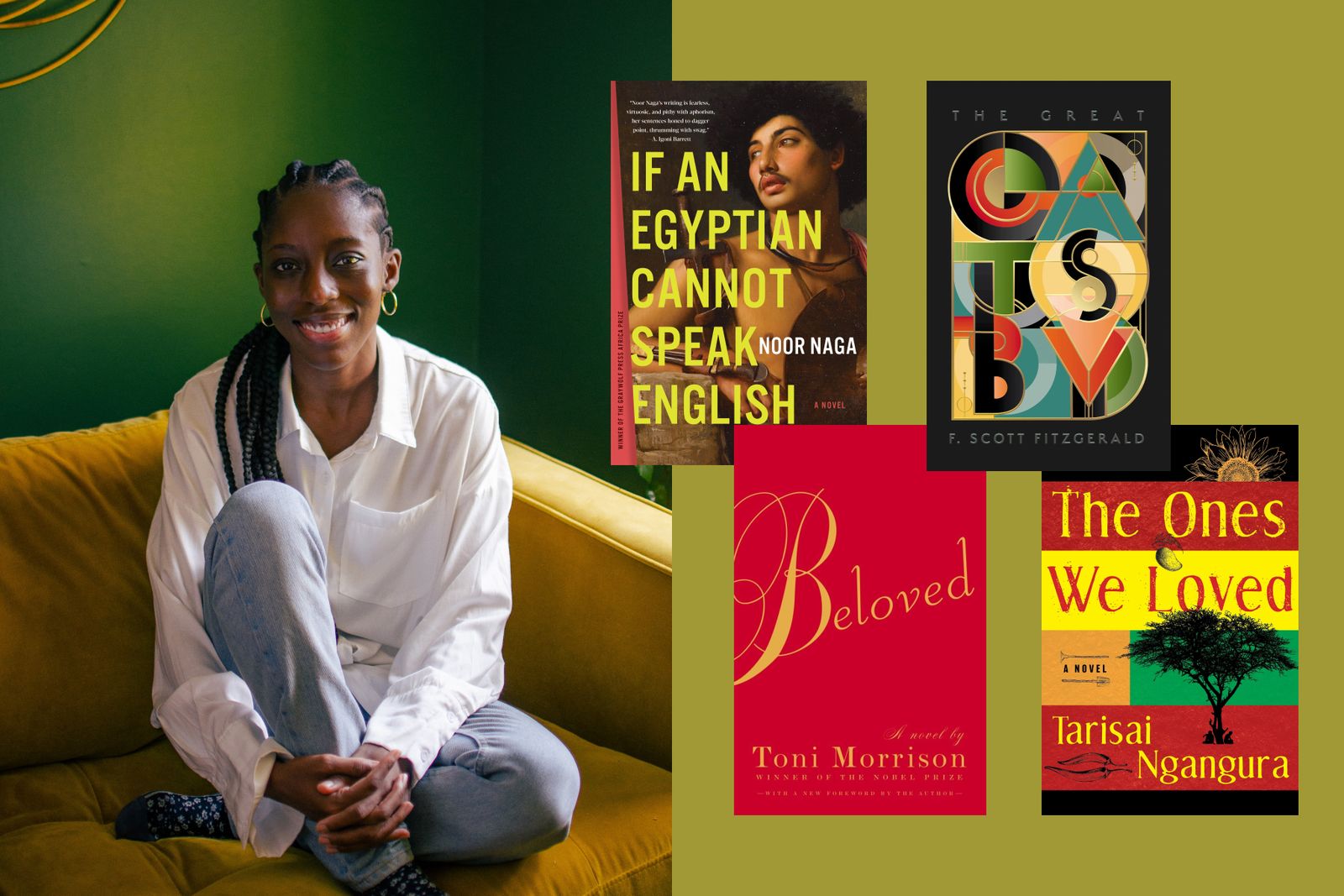

During the four years that I wandered in and out of my characters’ lives, helping them move furniture around and clear out the weeds in their yards, I started to think of the homes in some of my favorite books and what they told me about the tensions that define what it means to live in a certain place. I thought of the young woman in Noor Naga’s If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English, whose seventh-floor Cairo unit came with four balconies from where she could see “a canopy of bat-infested trees.” I believe you can never have too many balconies, however, as someone who sees bats primarily as rodents with wings, the idea of them infesting trees is so awful it makes me want to never step outside. Yet from her apartment, Naga’s character seeks out the bats and makes a routine of listening to them shriek as the sun starts to set. Away from this nightmare symphony, I was drawn to the character’s love affair with the random delights that littered her apartment: the hardbacks that rested on her shelves, “which, when opened, reveal ribbons and leaves pressed into their hearts,” the furniture that was positioned “as though for a portrait,” and the hidden orchids that she “feeds with an eyedropper.” The home’s scents and fabrics transmitted so much of the character’s way of life that while reading, it was difficult to imagine her ever leaving such soft familiarity. And yet she does. And I wondered what she took with her as a reminder and what she left behind.

In literature, the home is a place that shelters and reveals, and now that I’ve finished my novel, I am wondering what every home in a book can also say about the writer.

I have at times wished that my own home, a New York City apartment, was an object that I could easily reach for, something that I could fold up and carry with me. In the same way that I collect my skincare essentials into a palm-size purse and squeeze them into the smallest part of my suitcase when traveling, I have wanted to do the same with my home essentials: my roomy, velvet sofa that sparkles yellow when hit by sunlight and turns green when I close the blinds; the low, circular table covered in green and white square tiles that feel smooth when I brush them with my fingertips and become an ASMR dream when I brush over their ridges with my nails; my whole kitchen because it knows my mess; my apartment door with its old-fashioned lock and blueish patina. I have made this place my own not only because it’s my address and I pay for the utilities, but because a lot of the objects that enamored me while traveling are placed in different spots and shelves. As are the gifts from friends (sweetly personalized ceramics and knitted table mats) and my collection of teapots, along with the Oliver Mtukudzi vinyls from my capital-letter Home: Zimbabwe. Though the structure of the apartment encloses me, it is the memories within that keep me here and remind me of everywhere I’ve been and the places I left. This little gem in Harlem is my permanent place for my itinerant life.

In literature, the home is a place that shelters and reveals, and now that I’ve finished my novel, I am wondering what every home in a book can also say about the writer. Do authors construct their own concrete visions of home via the characters that we create, ones that we will inevitably leave behind once the book is finished? I have moved several times in my life, across continents and borders, and that’s likely why home is something I’ve always wanted to pack up with little trouble. But is it the only reason? In The Ones We Loved, although the characters’ homes were lived in and assiduously maintained, the characters’ love for the structures they built was somewhat hesitant. It was as though by fully claiming their homes as their own, their bodies would become fixed to their walls and unable to break away if the time called for departure. My characters are all prepared to leave, even when they’ve been somewhere for decades. Did this latent desire to look further speak of their interiority or mine?

In Morrison’s work, the home, whether a building, a country, or a person, is often able to transform even after seemingly insurmountable destruction. We can rebuild, and that is the sweetest part.

Many writers’ lives appear to split between their private interiors and their literary ones. F. Scott Fitzgerald stands as a curious example. In The Great Gatsby, the novel’s namesake has a magnificent home that is excessive both in its opulence and its absence of warmth. It’s so grand that it needs to be filled, and so grand that it will always feel empty. Fitzgerald only became rich in adulthood as his career expanded, and from his work it’s apparent he found the wealthy fascinating and pitiful. After he joined their ranks it must have been difficult to perceive himself as equal parts Jay Gatsby and Nick Carraway, chasing decadence and searching for a certain modesty. In his debut novel, This Side of Paradise, he observed the rituals of Jazz Age youth and their desires to be different from their parents while still enjoying similar comforts and freedoms. In thinking about home, a character says, “With people like us our home is where we are not.” Fitzgerald seemed to suggest that home was not a place but a constant longing, something fused to nostalgia and distance.

In Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Sweet Home is the name of the plantation where the main characters were once enslaved, and the site was a witness to their horrors and a place where they also shared laughter, memorable meals, and lifelong friendships. How does sweetness exist alongside the perverse brutality of being enslaved? On Christmas Day of 1993, Morrison’s upstate New York home burned down, with the only things remaining somewhat unscathed being her manuscripts and papers, which had been stored in a “special study”—a home within a home. The New York Times reported that the author was “upset over the loss of the house, but immensely relieved that her papers had been recovered.” There is a strange sweetness in that relief where one grieves a lost home and also celebrates a recovered treasure. In Morrison’s work, the home, whether a building, a country, or a person, is often able to transform even after seemingly insurmountable destruction. We can rebuild, and that is the sweetest part.

Toward the end of If an Egyptian Cannot Speak English, the canopy of trees infested by bats becomes the witness to a deadly event, and the geography guards the memory of a city and a young woman. In The Ones We Loved, a mango tree and a guava tree frame the characters’ choices regarding new beginnings and secrecy. In all the places I’ve lived, the flora in the city is what remembers me and keeps me there. It’s what pulls me close when I’m away—this constant renewal of life and the nature of belonging in places that you will always leave behind. Sometimes this quiet promise of recollection can falter when the trees and flowers that used to line your daily walks are replaced with parking lots and multiuse buildings, making it almost impossible to stake a presence in the places you love. I have slowly realized that my body is the only constant home, the place I will always sink into no matter which border I’ve crossed, and what I’ve gathered along the way. In writing and finishing my book I saw my characters returning to themselves and holding their bodies tightly, recognizing that belonging wasn’t something made possible by a location, but by how their bodies felt when they arrived, when they decided to finally rest, and when they began again.

Related Reading:

Home Renovation Shows Meet Cute with Romance Novels

A Love Letter to “Material World,” a ’90s Photo Book of Families With All of Their Possessions